Craftsmanship Soul - where craft hides – shining light on newly produced contemporary craft

30/04/2020

Craftsmanship Soul - where craft hides – shining light on newly produced contemporary craft

Where craft hides – shining light on newly produced contemporary craft

This article reflects upon the work of craft artists Giovanni Corvaja and Kazuhito Takadoi and highlights the unexpected approaches that they take to produce extraordinary contemporary craft.

Set in the beautiful location of Somerset House, central London, craft makers Giovanni Corvaja and Kazuhito Takadoi spoke about their work in conversation with Anatxu Zabalbeascoa, President of the foundation’s Craft Prize jury. The discussion was presented by Sheila Loewe, President of the LOEWE FOUNDATION and held as part of COLLECT 2020, an international art fair for modern craft and design.

Both craft artists are Loewe Foundation Craft Prize finalists, selected for the annual award in 2019. Though their body of work is very different from each other they greatly connect by the use of unconventional and unexpected methods which ultimately produce outstanding pieces of art. Together they will speak about some of the contradictions that relate to their work, illustrating the vast possibilities in contemporary crafts today.

Anatxu Zabalbeascoa began the conversation by explaining the Loewe Foundation’s idea of an international craft prize in 2016. In part, this was to change perceptions, by highlighting groundbreaking and innovative techniques. The definition of contemporary crafts in the 21st century is too often seen as a contradiction, meaning that to safeguard its deeply rooted traditions, craft has to modernise and just as importantly, celebrate it.

“That is why The Loewe Foundation Craft Prize supports craft artists all around the world by honouring 30 finalists every year for their unquestionable quality of work, their skills, and also for pushing the boundaries of tradition.”

Giovanni Corvaja is a goldsmith. He is renowned for his creations made of ultra-thin gold wire, ultimately treating the metal as natural fibre. Over many years he has researched and devised a technique that combines weaving, braiding and carpet-making creating objects made of gold, that are more likely associated with textile art than with traditional jewellery making.

Giovanni Corvaja, Ring ‘The Golden Fleece’, 2008, 18ct gold, 104,272 single wires

Kazuhito Takadoi creates intricate work made of natural materials, such as grass, leaves and twigs; selected from their abundance in his garden and allotment. Unique as his work is, he does not restrict himself to one particular plant material or process, instead, he experiments with weaving, stitching to paper or tying twigs into a structure with natural string amongst others.

Kazuhito Takadoi, Keiro (Path), 2019, grass and gold leaf on washi paper

For Giovanni there has been an early fascination with the lightness and transparency of glass, which he first came across in Venice when visiting his relatives as a boy. At the time, he expressed this lightness in line drawings, inspiring him to work with wire when making jewellery as part of his metalsmith training at Pietro Selvatico High School of Art in Padua, Italy. Step by step, he learned from his discoveries and soon began to make thin gold thread. Challenging himself as to how thin he could make them, the gold became so minuscule that the human eye was unable to focus on a single thread. He realised that by changing its density, the gold would lose its intrinsic qualities; it became soft, springy and light. Traditional ways of handling metal, such as hammering, forging and casting no longer applied.

Giovanni Corvaja, Headpiece and Pendant of The Golden Fleece Collection, 2007-2009

This revelation led to his treating the metal threads as textile fibres and he began to extensively study ways in which they were manufactured. “While researching I encountered the Greek mythology of the Golden Fleece” Giovanni explained. Symbolising the reward of a near-impossible task and in alchemical interpretations is used as a metaphor for divine art and transformation. His ambitions were now set on producing a collection of The Golden Fleece: a golden fur headpiece, ring, brooch, bracelet, and pendant which would exhibit the tactile qualities of fleece, while still retaining the intrinsic attributes of gold. Using an adapted version of the traditional Japanese braiding technique Komihimo, he wove each item by hand. For the headpiece alone, he used 160 km of superfine thread, spending 2,500 hours making it. “It is very intensive, very repetitive work, sometimes a bit tedious. And while I was working (already one year in the making), I started thinking and understood that I was working with a technique that in my head was already obsolete. It was in that moment that my mind was faster than my hands.”

During this process he improved his method of making the gold filaments even thinner. Now he had the possibility to make them up to 7 microns thin, that is, a 100th of a single human hair. As a result, he returned to a former idea, to weave a cloth. Seven months later he finished a gold square pocket, made from 18 and 20ct gold, using a simple loom and completed with hand-stitching.

The piece drapes smoothly, with the quality of silk, but retaining the metal’s temperature and weight. Even though those contradictions can be sensed, the feeling of an almost magical transformation prevails, that of precious, highly dense metal, being turned into a seemingly natural fibre.

Giovanni Corvaja, Golden Cloth, 2009/2010, 18 and 22ct gold, hand-woven golden fabric

Giovanni continued, that in order “to make gold thread in the density of 5-7 microns, the process has to be very clean. Because operating at this micro-scale, any form of dust or pollution will be far bigger than the gold fibres”. Cleanliness now became by far his main issue in the process of making. At the same time, it also presented a creative opportunity: the possibility of two similar metals under vacuum being joined to each other.

At that stage, he became eager to find a way which allowed him to work the gold threads under very clean, airless conditions. Years of experimentation later, he built a complex vacuum chamber used to produce the Mandala collection. “The condition inside the sphere is almost identical to the condition in space”, he proudly explained. It enabled him to create delicate structures made of ultra-thin gold wire, which under those extreme conditions adhere by contact alone. But his first experiment with a bowl failed as the piece lacked strength and he realised the need to create geometrical shapes within the object’s structure for it to become functional.

Giovanni applies a very complicated mathematical and geometrical design to arrange the wires into a multi-layered sculptural latticework. The adhering process takes about half a day to be completed when step by step he increases the degree of vacuum and very low temperature for the gold filaments to bond. The perfect symmetry of parameters allows the wires to join and the metal structure to warp into a bowl shape. To research and perfect this process it has taken him three years so Giovanni understandably considered that it “is a success from a technical point of view, but also from an aesthetic point of view”.

The Mandala Bowl fascinates simply due to its weight; around two-thirds of its volume is air. The geometrical structure invites light and gives a sense of transparency. It is a small, beautiful object that fits comfortably in the palm of one hand, weighing only 82grams and using about 4 km of thread.

Similarly, Kazuhito has found unexpected ways to produce his work, following his intuition and developing incredibly ornate pieces from materials that were abundantly available to him. By creating work that has never been made this way before, it is difficult to assign his craftsmanship to one craft category. The work can neither be described as woodcraft, weaving or traditional needlework. What he creates is made from natural resources found in his immediate surroundings. He then takes these materials and assembles them – branches, grasses, and reeds – to create forms that shift and change as they age.

Enjoying nature and gardening since his early childhood, while studying at The Royal Horticultural Society in the UK, Kazuhito would occupy himself with self-inspired art projects, collecting natural materials that he would find during visits to English gardens. He began to specialise in applying his work to a format of hand-made greeting cards, embroidering the paper imaginatively with natural materials. The feedback he received from family and friends encouraged him to continue and soon he developed his unique process of weaving twigs and grass on washi (Japanese hand-made paper) and gold leaf. He went on to enrol at Leeds Metropolitan University and graduated in 2003 with a BA Hons in Art and Garden Design.

Nature is both his inspiration and source of material. He now mostly uses organic resources grown in his small garden and allotment in the UK. The English weather and the natural beauty of habitat have heavily informed his work “Rather than controlling nature, I like to leave it to nature the way a twig will grow. My work does bridge the two cultures that I experience” but “point at a clear direction from where influence comes from is impossible”.

For ‘Kado’ (Angle), the sculpture which received a Special Mention at the Loewe Foundation Craft Prize 2019, Kazuhito used hawthorn twigs. He began with the basic shape by tying the hawthorn together with waxed linen twine and a pair of tweezers before filling the inner structure in the same way.

During his presentation at COLLECT, Kazuhito showed more images of his work and its variety, changing between different raw materials and processes.

Kazuhito’s pieces not only fascinate due their meticulous finish, but also the strong visual storytelling that he conveys within his compositions, such as a tree in the morning sun. He consciously creates tonal variations within the grasses to convey the contrast between shadow and light and when walking around the artwork, it seemingly moves with us.

For the collection of hawthorn twigs, he contrasts void and solid spaces within the structures. Each work keeps us captured because of the contradicting aesthetics within them; they appear minimal at first glance, yet the structures are complex. The strength of the solid structures is in direct contrast with the fragility and its constructed lightness.

His heritage is prevalent in Kauhito’s work, such as the use of washi, his memories of smells and the change of light witnessed when playing in Japanese woodlands as a boy. All are a huge inspiration in his work. Kazuhito admits though that developing techniques, styles, and processes has taken him a very long time “I believe this is a very Japanese way of doing things” and that, “There are plenty of setbacks within the work, such as harvesting hawthorn in February’s freezing winter cold or sewing with grass that keeps breaking. But in the end, it’s all worth it!”.

Kazuhito was unsure whether to submit Kado (Angel), the complex thorn sculpture to the Loewe Foundation Craft Prize. Under ‘category’ he selected ‘other’, wondering whether its submission was validated. “I was not sure if my art will be accepted, but allowed myself to be persuaded” he explained with charm and no little humility. When shortlisted, he was, by his own admission, extremely, surprised. The honour of Special Mention by the Loewe Foundation undoubtedly gave him the acknowledgement of being an extraordinary artist amongst his contemporaries in the craft world and his gratitude for such support, after a long, solitary journey, was tangible to all who attended.

During the discussion, Anatxu questioned whether cultural background and craft correlate, and asked Giovanni and Kazuhito “How important is your own biography to your work and how much does it reflect in your craft?” Both agreed that every career step of a craftsperson affects their artwork in some way “All I know about how to do something is because of what I have learnt from other people and particularly from the people around me”, Giovanni commented, reflecting on his passion for Venice glass, which has influenced him since childhood. “I do put things together in my work. I don’t think I invent things. I adapt laboratory equipment to my use. So yes, the environment I am in is very important and influential to my work”. Kazuhito was of a similar view and referred to the training he enjoyed in Japan, the UK and also the US. “All the experiences having studied horticulture and also Ikebana (Japanese flower arrangement) gave me huge knowledge about the materials that I am using” learning, Kazuhito said, “provides the support to be creative.”

For the artists, their work being presented in the UK points to the fact that above all else, craftsmanship has no boundaries. The opportunities presented by globalisation make for their unique life experiences, reflected in art, design and crafts alike. It is evident that classifications in general are outdated as there is a constantly evolving aspect which accompanies and informs the subject. Where crafts have previously been strictly categorised, today, they boldly mix cultures, materials, techniques, and technology.

Not being scared of breaking existing boundaries, Giovanni admits to having naturally an endless curiosity and a never-ending thirst to learn. It drives him to experiment with new processes in every collection. From a final idea clear in his mind he develops his methods. What remains a constant is the love for gold. “I still have a lot to discover…I keep learning from it and there is still so much to do”.

For both, it transpires, the awareness of boundaries does not exist in this context. Instead, they are led by their inspirations, by curiosity, by intuition and by the joy in creating. What are considered to be restrictions or limitations are our prescribed specifications and standards. “I just make my work” said Kazuhito “I did not feel having boundaries. I simply tried new techniques. When I saw that people liked what I did, it gave me the freedom and the encouragement to think about it all the time”.

As the talk concluded, perhaps it is Giovanni’s words that are worth remembering “The most important aspect is to put your individual touch to the piece. That is what will break boundaries. It is not just the mind and the hands, but also the soul and the heart that make a piece extraordinary”,

Thank you to Sheila Loewe for allowing me to record the conversation and to write this article.

Thank you also to Giovanni Corvaja, Kazuhito Takadoi, jaggedart and the Loewe Foundation in supporting this article and for providing all images.

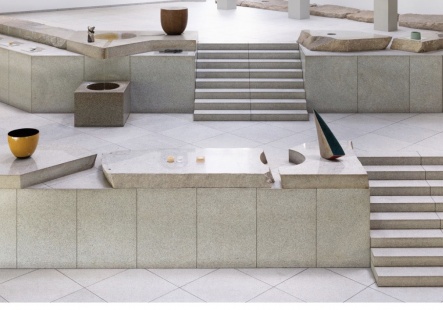

The cover image is from the Loewe Foundation Craft Prize exhibition at Isamu Noguchi’s indoor stone garden ‘Heaven’ inside the Sogetsu Kaikan building in Tokyo 2019.